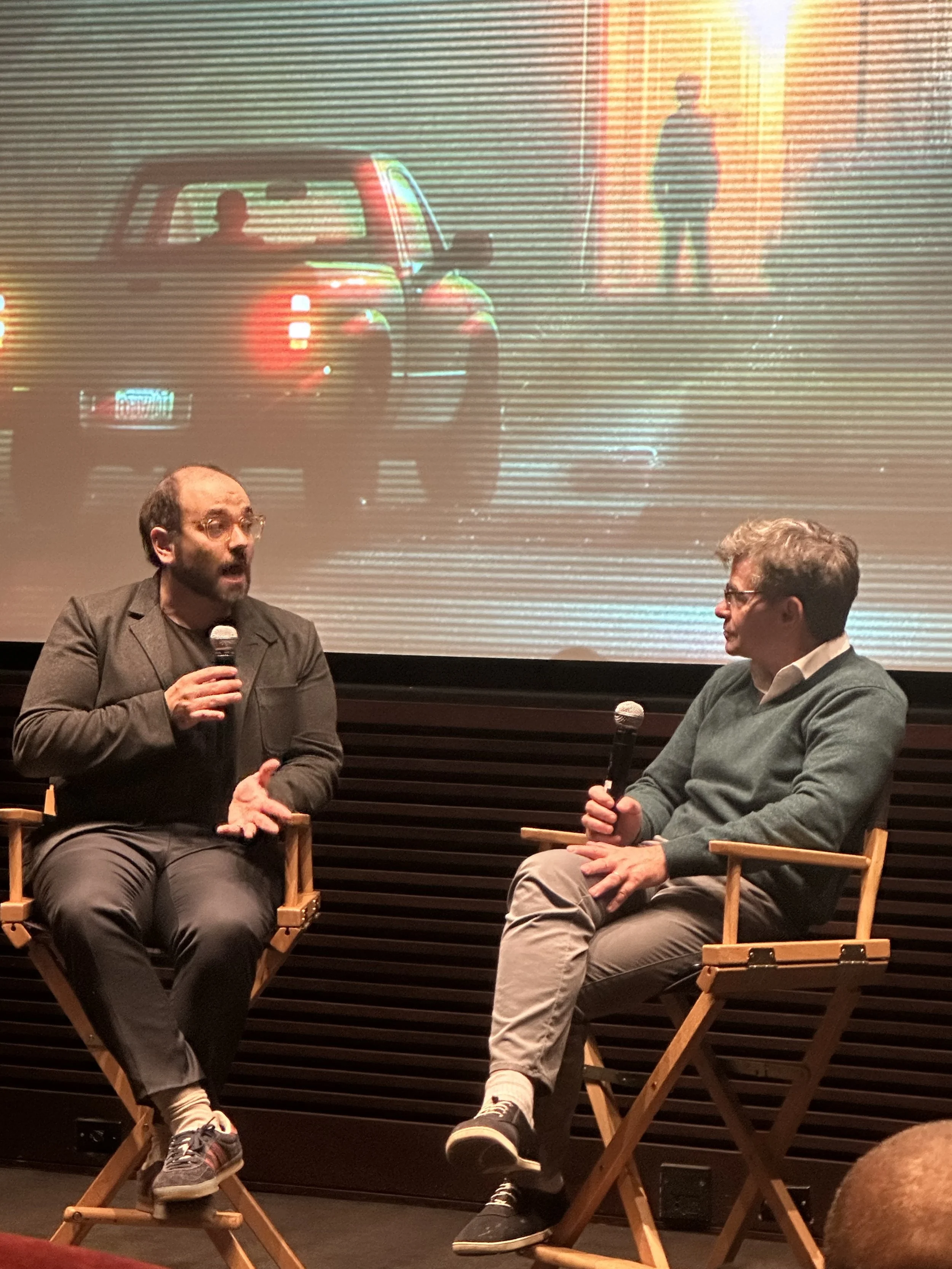

David Osit and George Stephanopoulos discuss Predators

David Osit and George Stephanopoulos discuss Predators at the Paramount Screening Room

It’s awards / Q&A season, with countless invite-only screenings and discussions, including celebrities if possible. I was lucky to attend one of these, for David Osit’s extraordinary and purposely unsettling documentary Predators. The film is about the blurred lines between entertainment and journalism, and about the vast gray areas regarding morality, voyeurism, empathy, and exploitation, that come with the territory of TV journalism and documentary film, forms that often enter murky terrain while claiming to offer black-and-white answers. Osit is an incredibly thoughtful independent documentary filmmaker, and I’ve been wanting to see Predators since it premiered at Sundance. I admit I was lured to a screening by the participation of George Stephanopoulos, a hero from the halcyon days of the 1992 Clinton-Gore campaign. As it turned out, Stephanopoulos, an incisive and engaging interviewer, was the perfect moderator for the Q&A, eliciting fascinating answers from Osit but also offering his own perspective from the world of network television.

“Children for Sale” was the title of the 2004 Dateline segment in which reporter Chris Hansen went to Cambodia to expose American men who had traveled there to buy sex with underage girls. Ambushing these perpetrators Candid Camera-style, exposing their sordid behavior to the glare of the TV camera for a national audience, and rescuing the girls from their exploitation, made for a riveting blend of righteous journalism and thrilling television. Sure enough, Hansen quickly embraced the role of vigilante Allen Funt, packaging his sting-operation tactics for the popular NBC series To Catch a Predator, which launched just months later. Filming closer to Kansas than Cambodia, he scoured the American heartland for sexual deviants. Typically, the setting for each episode’s harrowing, often life-wrecking confrontation between Hansen and would-be predator, was a nondescript suburban home in a seemingly quiet neighborhood.

Osit’s astonishingly complex documentary Predators quickly draws us in to the undeniable dramatic power of Hansen’s enterprise, only to raise thorny questions lying beneath the seeming heroics. Claiming that “the law is the law,” and that his goals are entirely virtuous, Hansen diverts us from thinking about any lines he might be crossing, and about anything dubious in the show’s irresistible blend of moral certitude and lurid entertainment. Ultimately, Predators makes us examine what lies behind the thrill of Hansen’s trademark move; telling his subjects that they are “free to go” after an interview, sending them to their doom as a group of armed police await them on the other side of the door.

In the 20-minute Q&A Stephanopoulos had great questions. And like the best documentaries, Osit’s film raised its own question rather than providing simple answers. To Catch a Predator was cancelled in 2008 (after one of his targets committed suicide), but Hansen went on to become a YouTube, streaming, and podcast star. Inevitably, his approach crossed the line of fairness, as in the case of Hunter, discussed below, an 18-year-old who was seeking sex with a teenager just two years younger, behavior that was legal in some states but not others.

Here is the discussion between Osit and Stephanopoulos in its entirety:

George Stephanopoulos: I saw the film about two months ago, was riveted, and just watched the last half hour again. So I'm going to begin where the movie ends. I need to know, what was going through your mind when Chris Hansen says “I did this for you?” [After Osit revealed to Hansen that he was a victim of abuse as a child.]

David Osit: Yeah, I spoke to Chris long before I filmed him. I couldn't imagine the film without him, without one day interviewing him with a hidden camera, and telling him he was free to go.

George Stephanopoulos: They were hidden cameras, but he knew.

David Osit: Obviously he knew, but I knew that I had this construct that I was pursuing but I didn't really know why yet. I understood that it would be interesting to have a paradigm where he's looked at in the film, with all the ambiguity that the word predator has and all the ambiguity that the word victim has, and the film is really living in that gray space. But I had seen him speak so many times and seen so many interviews, that I knew he was never going to surprise me with with what he would say because he has never really been asked to be accountable for any of this work. He is on the side of good, he's doing an unimpeachably good thing and he's had a whole career of being supported and endorsed for what he's done and now that he's on the internet and no longer part of a major news network he has even more affirmation for what he does, and there's a lot of value to the things that he does, I'm not trying to say there's not a value to it but I think that when he said that to me, I heard it as a sort of pat binary of good and evil.

George Stephanopoulos: So it wasn't personal to you.

David Osit: It didn't feel personal at all to me. It feels like actually the justification that he needs to continue doing what he does, because someone's getting healing out of it. But I debate the idea that maybe there's a world where just because we feel healed doesn't mean we are, and I think that that's what a lot of true crime and reality tv kind of helps us feel, but I doubt the efficacy sometimes.

George Stephanopoulos: You know I've done thousands of interviews. I know what it's like to sit across from someone who is very uncomfortable when they're getting questioned. He was not comfortable at all. So do you believe he believes his own–I’ll say patter, not bullshit.

David Osit: I’ve never met someone who does what we do for a living, I say “we” in a broad sense, journalists, filmmakers, who doesn’t believe they’re right. I don’t know if you have. I think everyone basically believes their stuff.

George Stephanopoulos: Except as soon as you say that–I believe it too–as soon as you say that I go straight to Janet Malcolm who says that every journalist is a con man.

David Osit: Sometimes it depends on who the con is for, right? I think that you can delude yourself or you can convince yourself of certain truths till they become true, but I'll tell you when I watch the Cambodia material that Chris did, that line is not crossed for me. I like what he's doing there. I appreciate the value of that. Of course, there's a key difference is that there's victims, actual victims in that.

George Stephanopoulos: That's where I think the movie is fair to him. That is unimpeachable good you're seeing in 2004.

David Osit: You're also seeing a man's full name being broadcast, his life lit up permanently, but it doesn’t cross the line for me. And for me the film is kind of living in a little bit of that gray space of where do we decide how much empathy or cruelty we're capable of and for what cause and for what reason.

George Stephanopoulos: And you swing back and forth between it through the whole film.

David Osit: I do and I think as a result you do because i really tried to make a film that was modeling an experience that I was having, for an audience to have it too. Which is why sometimes it's uncomfortable, it's why sometimes you don't like me, or what I'm asking you to think about or do. Because I think we watch a lot of documentaries and a lot of documentaries exist that are designed to just affirm you. You watch it, you know it's going to be in agreement with you, it's going to make you more angry about the thing you were already angry about, the film's over, you've got more anger, you’re affirmed in your anger, you're good because you watch the movie. The bad people are on the screen.

George Stephanopoulos: And it's built into the whole enterprise that you've engaged in here. You're participating in what you're critiquing.

David Osit: Yes, and that was an uncomfortable part of the filmmaking for me, to realize that the heritage of what I do for a living is not immune from criticism. And that's part of the reason for the release form moment in the film, which is pretty fundamental to my understanding of trying to differentiate myself in some way from what I was filming, but in the process of doing that, becoming very much a part of it.

George Stephanopoulos: So talk about how this all began.

David Osit: I was never thinking of making a film about To Catch a Predator. That wasn't on my mind or on my doc film wish list. But one day I discovered the online fandom community for the show.

George Stephanopoulos: So that was the beginning.

David Osit: That was really the beginning.

George Stephanopoulos: You watched it as a kid.

David Osit: To go back a little bit earlier, I watched it as a kid, but I didn't think anything of it. It was just a show that was on. And then the pandemic. I had a film that was called Mayor, which came out during the pandemic. And it did well, but it was virtual and during that time the only films that people really were doing pitches, soliciting pitches for were true crime projects. I couldn't get anyone's attention unless it was true crime. So in the back of my mind I was always thinking it would be great if someday I could find a true crime film I wanted to actually make. But I can't imagine finding one. Maybe I can find one that's about how much I don't like true crime.

George Stephanopoulos: I actually want to press that because it's something I live in every day on Good Morning America. Basically, if you're tuning in at 7.30…at 7 you know you're going to get the news. At 8 o'clock you're going to start to get entertainment and consumer stuff. You know you're going to be getting a true crime story, maybe two or three, at 7.30. When we deviate from that formula, the audience goes away.

David Osit: You've noticed that? That actually when your, like, audience numbers drop off if there’s not a true crime story?

George Stephanopoulos: Oh, 1,000%. They notice everything. So talk a little bit about this fascination with true crime, because it's the same thing. In our documentary units at ABC, you know, four out of five are true crime. That’s inexact but it’s something like that.

David Osit: We like good versus evil stories, especially in fractured times. I think in a society that’s bursting at the seams, with deplorable behavior, and we have police. On a societal level, not an an individual level, we like—and there are certain politicians who campaign on—the premise of law and order and providing protection from the world of deviant behavior and reinforcing that.

George Stephanopoulos: And this need for scapegoats that can symbolize finding some kind of justice.

David Osit: Chris's colleague Sean puts it quite well in the film. He's like, why do people watch true crime? It's better them than us. My life might be really bad but I’m not a predator. It’s way to find comfort in some of these situations. And it's not always as sordid as that for people who are watching it, but it is a simple story with a simple resolution that you're always going to be on the right side of. That's, I think, the appeal of true crime.

George Stephanopoulos: So you learn about these online communities. How does the film build from there?

David Osit: They had been for twenty years collecting raw footage from the show. Very small, but very passionate group of fans of the show who had found all this raw material, the opening of the film, the first elements of the film, it's entirely from the footage that they've found, from depositions, through FOIA requests, through client defense packages. And I watched that footage remembering the show, but I watched that raw footage and I was horrified. I was horrified by lots of things. I was horrified by how I was feeling watching it. I was horrified that I would feel bad for these guys. I was horrified by the things that they would say. I was horrified by the sensation of watching someone's life end in slow motion that way. And I thought, well, the show didn't make me feel anything. There was the inversion of emotion.

George Stephanopoulos: So all the grey comes out of To Catch a Predator.

David Osit: Absolutely. And in a lot of true crime shows. But the thing that was interesting about To Catch a Predator twenty years ago, I would argue that back then, there wasn't really a thing where journalism and law enforcement would work together to create entertainment. That wasn't a model that existed, and now, of course, it's ubiquitous. But back then, you had your journalism programs, and you had…

George Stephanopoulos: It might lead to something later.

David Osit: Right. But true crime wasn't a genre back then. Something would happen and then it would be reported on but it wasn't a genre because we didn't have a language for it because we didn't understand yet that you could play with the idea of, is it entertainment or is it journalism. And with Cops for example, no one was presenting that as journalism there. It was not a news program, back then you know there was Dateline, 20/20.

George Stephanopoulos: But those shows, I mean if you look back at the history of those shows they didn't start out as true crime shows. They morphed into almost entirely true crime shows because the audience was telling them, if you give us this, we're going to give you back our views.

David Osit: Exactly, and I think that at a certain point, it's nighttime, and we don't have the watershed in the same way as they do in the UK, but past a certain time of night, you can show things, and it starts to entertain people. The numbers go up, and I think that then speaks for itself.

George Stephanopoulos: How much changed with the iPhone?

David Osit: It maybe goes without saying, but now everyone can be their own content creator, so there's not a huge difference between Skeet Hansen and Chris Hansen in the sense that they both have their own networks now. Like, they don't need a news program or the legal assistance of a news division for this type of work anymore because no one's ever really cared about the men that they would catch in terms of legal situations, but also that they're protected, they're able to do what they do.

George Stephanopoulos: I was thinking about it when I was watching, again, the end, if, and I'm pretty sure I know the answer to it, but I'm not positive. I don't think the Hunter story would make it on Dateline or 20/20.

David Osit: You know more about that world than I do, but I could imagine that there's a level of gray area there that there is enough doubt as to how we define the word victim that I think it becomes complicated for the typical auspices of a true crime show.

George Stephanopoulos: I'm forgetting his name, but do you think Chris's partner truly didn't want to air it?

David Osit: Yeah, I do. I do feel that way, and I think that ultimately that was a hard fought battle for him to convince Chris not to.

George Stephanopoulos: The scene with Hunter's mom when you're hearing him through the bedroom wall is just heartbreaking. Have you heard from her, from him, from any of the other people you've portrayed in the movie?

David Osit: Yeah, I'm really grateful that everyone in the film liked it. Chris saw the film right before Sundance. He had me on his podcast last month called Have a Seat with Chris Hansen. So if anyone needs more content, it's out there. T Coy, the female decoy who works with Skeet, she came to Sundance and saw it there. She watched it a couple more times since. Skeet just saw it and called it on social media a banger. So I think that this film might be a Rorschach test for certain people. I think everything is, really. But I've noticed very different reactions to the film because I think it really depends on what your interest is in going to some of the places that the film goes to.

George Stephanopoulos: I just want to ask one more question about Chris. So he has you on, he says he liked it. Do you think he's decided the best defense is a good offense, or do you think it's just so easy for him to always go back to 2004 in Cambodia and say, that's who I am?

David Osit: I think both things might be true. I don't think they're mutually exclusive when it comes to him. I think that he has, as you do, a thick skin, and you have to. And I think that he's turned that into a skin so thick it consumes the arrows and turns them into more fuel rather than repels them I think that he's quite adept at doing what I think a lot of expert rhetorical politicians can do which is that if they're disagreeing with what I'm doing it means that they're the enemy I mean they're the problem. He would not say that I am and he's from Michigan so he’s polite so he’s not going to come out and actively say that he's got a problem with some of these things. There's people who have been a lot worse to him than I have. I'm not mentioning the fact that he was arrested for something twice in the film. I focus on the work that he's doing and I'm frankly doing what I wanted the show to do what I would want lots of shows to do which is to genuinely give people space to talk.

George Stephanopoulos: When you imagine everybody here leaving today having a conversation about the film, what do you want that conversation to be about?

David Osit: It’s a good question because I don’t want to tell you. This question gets asked of documentaries, it doesn’t get asked of fiction. In fiction, we're more used to a film being about the experience of going through something emotionally that you watch that's almost unquantifiable and confusing, and you have to live with it, and it crawls under your skin, and maybe you dream about it, or maybe you don't, but there's times when you have experience with a movie and it stays with you, and documentary, more often than not, is the providence of, I have answers for you, and I'm going to solve child predation. I'm going to fix... this issue.

George Stephanopoulos: You're going to put someone in jail.

David Osit: Yeah, you're right. This is a problem. And because you watch the film, you now kind of can see who the good guys and the bad guys are. But I think the reason I don't have a specific thing that I want people to talk about is that I just want you to see yourself in the movie. And you can identify with anyone in the film, I think, if I did my job.

George Stephanopoulos: My hunch is you have succeeded.